Gutenberg's development of movable type in the 15th century was probably the most influential European invention of the second millennium. It paved the way for mass production, and the revolution is continuing in the digital age. Movable type has got more movable as it migrates into computers, mobile phones and e-reader devices. Having begun as an illuminated manuscript read by an elite few, the book may one day not exist in physical form yet be read by billions on mobile devices.

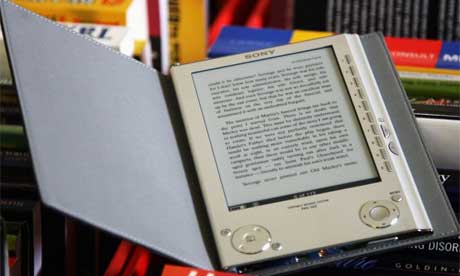

The Sony Reader ebook. Photograph: Chris Jackson/Getty

We are so used to digital miracles we have become blasé. It passed almost without notice that, at least in the US and Canada, up to a million Google-scanned books can now be read on Sony's ebook device, the Reader. Amazing. This is thanks to Google's ambition to scan as many books in the world as the lawyers will allow it to. You don't have to read them on a mobile device as you can buy them if in print – or, if you are masochistic, read them on a computer screen or print them through a print-on-demand website. However, the more I read on mobiles, as long as they have a big screen, the more I like it. You don't get the unique pleasure of reading a real book but you can take it with you, read in unusual places and write notes with one hand while holding the phone in another.

The reaction of publishing companies to the digital revolution was almost as antediluvian as the music industry's. Their failure to think about building a system to deliver books to readers enabled Amazon to do it for them. Publishers' response to Google digitising books was, like the music industry's, to reach for their lawyers. With honourable exceptions, most of the new ways of reading – especially the dedicated ebook readers such as those from Sony, Amazon's Kindle, and a slew of iPhone and Google apps – have been created by outsiders.

This has resulted in near-monopolies for Google and Amazon, which now owns both Audible.com (the site that has over 90% of the audio book market) and AbeBooks.com, the biggest online seller of secondhand books. Such concentration of power is one reason that book buyers have yet to benefit from the really low prices that ought to follow from the near-zero costs of digital delivery. What's more, with digital delivery, you are not buying a book you can lend to others but the right to read it on a device – with the risk, as happened with Amazon over Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four, that it might be withdrawn without your knowledge because it breached outdated copyright laws. What's that doing in the new age of continuous creation and remixing?

If book ownership is in danger of waning, book reading could increase thanks to a plethora of new devices. Amazon has a bigger Kindle e-reader, while Sony is about to launch two improved products. At the level of the phone there are lots of new readers for the iPhone, Android and other app shops to give the likes of Stanza, Book Search (which gives access to up to a million Google-scanned books from the web), Classics and eReader a run for their money.

The publisher Canongate is about to release an iPhone version of the rock star Nick Cave's new novel, The Death of Bunny Munro, created with Enhanced Editions to incorporate audio and video of the author. This is part a new genre of multimedia books from the likes of vook.com (still in testing mode) that brings video and books together on the web. Kate Pullinger's latest novel about 1860s Egypt is being accompanied by a virtual book tour during which readers question her online. Apple's rumoured iPhone tablet with a 10-inch screen should make reading more pleasurable than the much smaller iPhone. Its back-lit LCD will put it at a disadvantage compared with e-paper readers that can be used in bright sunlight. On the other hand, it will be in colour. Perfect for reading one of those medieval illuminated manuscripts. But this is where we came in.

No comments:

Post a Comment